|

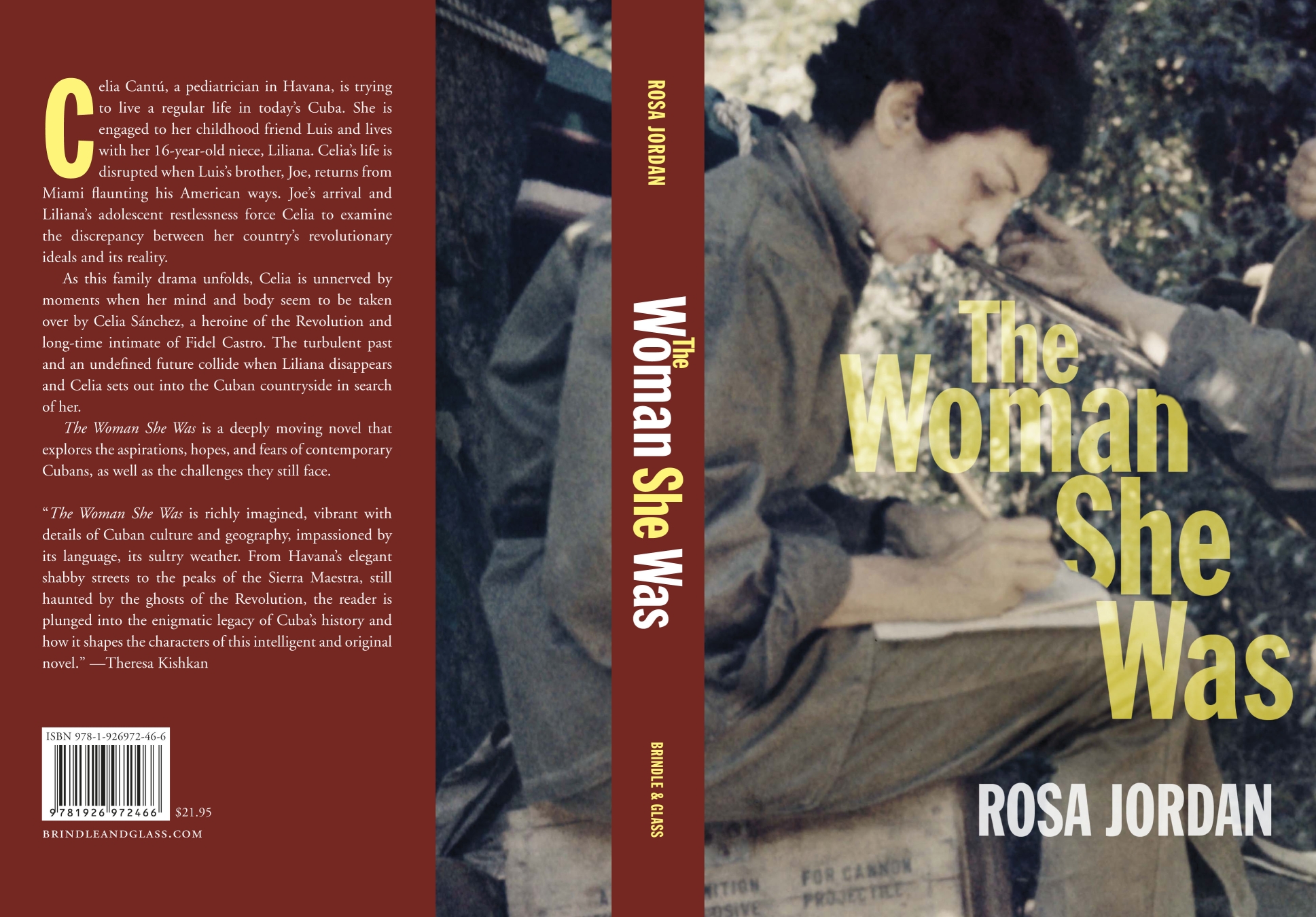

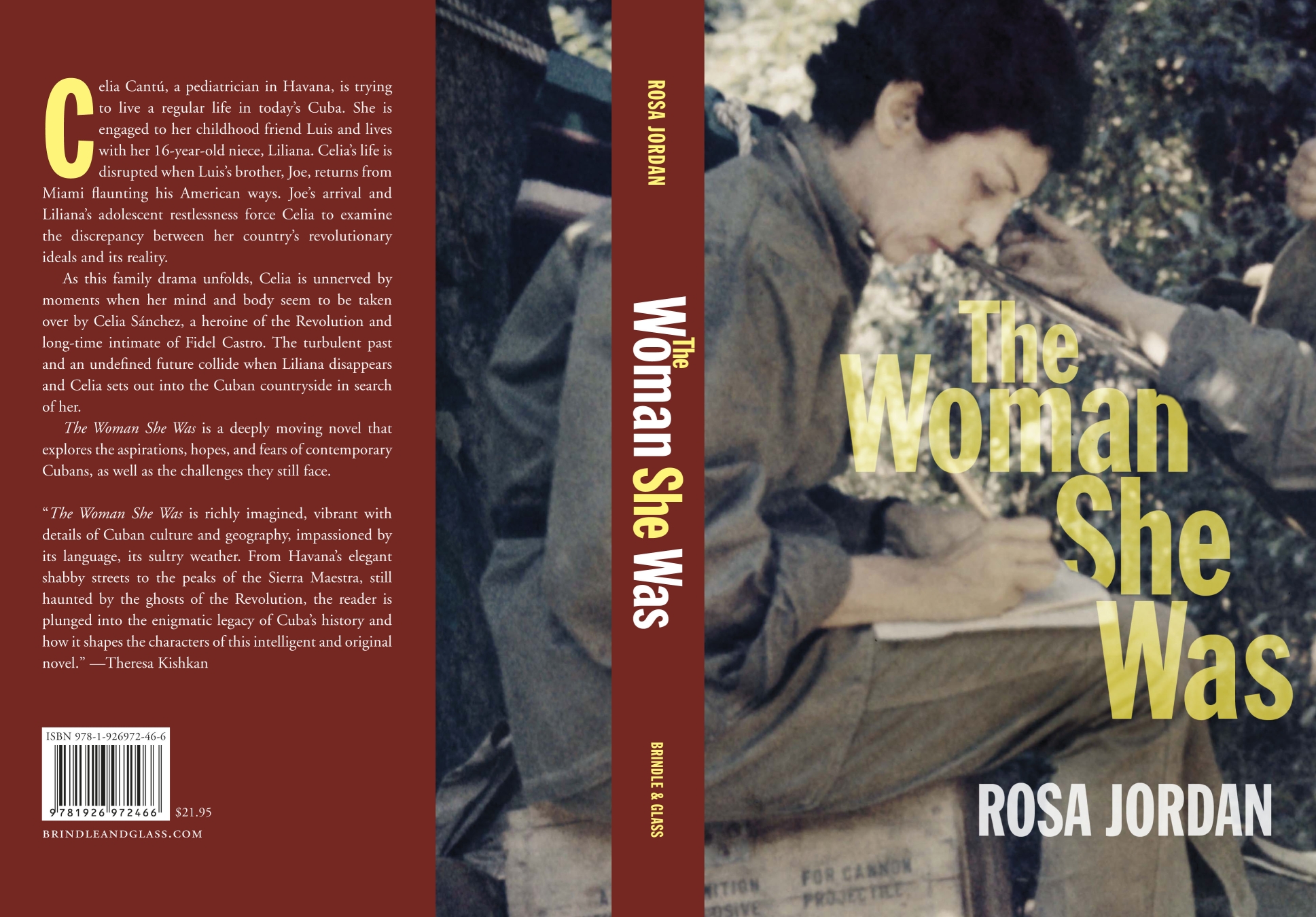

THE WOMAN SHE WAS

Why

did I

choose to write

The Woman She Was?

I have loved Cuba since my first visit there 15 years ago, and continue

to be intrigued by its complexities. I am especially interested in the

relationship between ordinary Cubans and their revolutionary history,

which frequently conflicts with their desire to move forward into

modern times. I hoped that by writing about some of these

contradictions, which I have heard in conversations with hundreds of

Cubans, that readers would come to realize that Cuba is not all about

politics and monuments to the past or a headlong rush to modernize or

leave. I thought that a good (but complicated) love story would be the

right vehicle for engaging readers, particularly those who hope to

visit Cuba and want more insight into the culture than what is

accessible during a brief vacation.

I chose settings that visitors to the island will

be familiar

with or could easily visit, but showed those places through the eyes of

Cubans. Of course, not all Cubans relate to their island in the same

way. Luis Lago is proud of what the Cuban government has done in

developing big international resorts like Varadero. His brother José is

both impressed by the modernization that has occurred during the decade

he has been away and disgusted by the decay of once-magnificent

mansions. Young Liliana sees resorts as places that offer fun and

freedom (not to mention an opportunity to earn money,) while Celia

abhors resort culture, which she feels seduces Cuban young people and

corrupts their values. The story leaves it up to us to imagine how all

those views of resort culture differ from how we as visitors experience

it.

Where did my characters

come from?

The first character in this story to enter my consciousness was a real

person—Celia Sánchez who for 22 years was Fidel Castro’s chief advisor,

confidant, and lover. Largely overlooked by historians, she was a very

private person, granted no interviews, and is little known outside

Cuba. I wanted to make Sánchez’s story more known but did not feel

qualified to write a biography; thus I chose to provide glimpses of her

through the mind of a Cuban woman who is named for her and, like me, is

uncertain of how much of what she has heard is true. That led to the

creation of the story’s protagonist, Dr. Celia Cantú, who feels a deep

connection to Sánchez and perhaps wishes she was Sánchez.

The Lago brothers are composites of many Cubans I

have met,

both ones who have left Cuba in order to get rich in El Norte and ones

who have remained loyal to their homeland and would not consider

leaving. The Lago brothers’ mother Alma represents an older generation

of Cubans whose values revolve around family and religious beliefs, not

politics. Meanwhile, sixteeen-year-old Liliana exhibits the attitudes

of many modern Cuban kids who take their social benefits for granted

and are hungry for cars, high-tech toys, and other consumer goods.

Another character I have threaded through the story, influential but

offstage, is Luis Posada Carilles. Like Celia Sánchez, he is a real

person. But while Sánchez died in 1980, Posada Carilles is alive and

well. His CIA training and terrorist activities against Cuba, including

the bombing of an airliner carrying the entire Cuban fencing team, are

well known. He himself bragged about that and subsequent bombings of

Cuban hotels in an interview with the New York Times and other media.

Although wanted for terrorism in three countries, he still lives

comfortably in Miami. Details about Posada Carilles included in my

story are true and well documented.

What does the title mean?

Every woman is the woman she was, the woman she is, and the woman she

wants to be. It often takes an examination of who we once were to

understand who we are now and who we have the potential of becoming.

The trick is to examine that past self without getting lost in

nostalgia for a glorious (but lost) youth; rather, to learn from it

what we are capable of in the here and now—or if the here and now is

not quite up to snuff, what we might become in the future. It is not

only Celia Cantú who faces this challenge, but also the nation of Cuba.

The “she” in the title is as much Cuba as it is the story’s two Celias.

Where

do my

ideas come from?

One part of my brain asks questions. The other part tells stories in an

attempt to answer those questions.

Questions

for

discussion

Do you think Celia would have been truly happy with either Luis Lago or

his brother José? Why or why not? What about her boss, the widower Dr.

Leyva? Might he have been a better partner than the one she ultimately

chose?

Do you think Dr. Leyva’s speculation as to why one of his daughters

became a bolsera, and Celia’s conclusion as to why her niece might have

wanted to become a jinetera, ring true? And if so, do you think the

same motivations of boredom, lack of opportunity, and materialism might

apply to young people in our own society?

Is Celia right to feel angry that so many doctors at her hospital have

left their profession to work in tourism where they can earn more

money? Should the Cuban government allow doctors who have been educated

right through medical school at state expense to leave the island (or

switch to jobs where their training is wasted) before they have repaid

the cost of their education by working several years in the Cuban

health system?

How do you suppose the average Cuban’s feelings are influenced by being

located barely 100 km from one of the richest countries on earth (where

many of their relatives live), and about the same distance from Haiti,

one of the poorest countries in the world (where many Cuban medical

professionals provide volunteer health care)?

We think of Cuba as being “Spanish” because the island was long a

Spanish colony and its language is Spanish. Yet Cuba has seen its share

of immigration. Based on the story, what other cultural influences can

be detected in the island’s culture?

About a third of Cuba’s population has some African heritage. There are

several black characters in the story—Celia’s best friend Franci, who

is a psychiatrist, the unhelpful administrator at Liliana’s school, the

nurse Orquida, an old man and a young Rastafarian musician in Santiago,

and the Haitian refugee child Josephine. Can you deduce anything about

race relations in Cuba from the way they are portrayed?

Useful for a book club

discussion about The Woman She Was

A large map of Cuba could be used for tracking the travels of the

protagonist around the island, which is almost 1000 km long. Note that

there are several mountain ranges. The most rugged is the Sierra

Maestra range, where Celia finds…what?

The story takes place in 2004, the last year that Cuba used

the US

dollar as an official currency.

Anyone with a particular interest in Celia Sánchez might want to read

the brief article, “A Butterfly Against Stalin,” by Celia Hart, whose

family was very close to Celia Sánchez. http://www.laborstandard.org/Venezuela/Celia_H_on_Two_Women_Leaders.htm

Also, a short essay about Sánchez

and

how modern Cubans feel about her appeared in the September 2012 issue

of BC Bookworld. A longer piece

about her is included in Rosa Jordan’s new book, Island Embrace: Cuba

Unspun. (Oolichan

Books)

The

Story

The Woman She Was tells of 35-year-old Celia Cantú, a Cuban

paediatrician whose day-to-day life is unremarkable—or so it seems on

the surface. She lives in a somewhat rundown apartment in East Havana

and is engaged to Luis Lago, a high-level member of the Cuban

government she has known since childhood. She enjoys her work and

adores Liliana, the 16-year-old niece she is raising. But three things

are about to shatter the serene surface of her life. One is the return

of her fiancé’s younger brother José Lago, to whom Celia was engaged

back in medical school but broke up with when he decided to immigrate

to the US. Now affluent and recently divorced, José is returning to

line up business opportunities in what he hopes will soon be a

capitalist, consumer-hungry Cuba.

However, Celia is less upset by José’s return than by hallucinations she has begun to have wherein, for a few seconds at a time, she feels as if she is not herself but Celia Sánchez, the revolutionary heroine for whom she was named. She considers these mental aberrations abnormal but hesitates to seek psychiatric help. Instead, she decides to visit the historic headquarters of the Cuban revolutionary army where Celia Sánchez lived (with Fidel Castro) during the war. Celia Cantú reaches La Comandancia, high in the Sierra Maestra mountains, where she has an encounter with a man that deepens her doubts about her own sanity.

She returns to Havana hoping for normalcy, only to discover that her niece has been skipping school and hanging out in resort areas doing things Celia cannot bear to contemplate. Before she can have a heart-to-heart talk with Liliana, the girl disappears. Although the Lago brothers try to help, Celia, for various reasons, blames them for the girl’s disappearance and refuses to speak to them. She goes in search of Liliana—a trip that takes her through some of the island’s most popular resorts and ultimately back into the mountains where she tries to sort out who she is—or was. And to understand where she—or her country—went so wrong that a much-loved child could go missing.

Not until things are physically exploding around her does she begin to understand who Celia Sánchez was, who her niece wants to become, and who she herself really is.

Author’s

personal background

I grew up in the Florida everglades, dropped out of high school at age

15, and had a child. At age 26 I entered college in California. (In

those days California colleges were nearly free so anybody who could

make the grades could easily get a university education.) After I

graduated from UCLA with a degree in international relations, my

daughter and I moved to Mexico for a year. Later I travelled

extensively in Latin America, often writing articles for newspapers and

magazines to finance my trips. In 1974, sickened by what I saw of the

harm done by US policies in Latin America, I moved to British Columbia.

Six years later I became a landed immigrant, and then became a citizen

of Canada. I didn’t write my first book until I was fully settled in

British Columbia in a home in the forest that my Canadian partner Derek

Choukalos and I built ourselves. We live, write, read, ski, and cycle in

the

Kootenays.

In the late 1990s I made my first trip to Cuba. Other trips followed when Derek and I accepted an assignment from Lonely Planet to write a cycling guide to Cuba. We have collaborated on two other books, a history of our town here in the Kootenays and a guide called Cuba’s Best Beaches. I also wrote a TV movie script, The Sweetest Gift, and four books for middle school readers, most with environmental themes. My most recent book, Cuba Unspun, was published in December 2012. It is a non-fiction account of my travels in Cuba during the past fifteen years.

I am often

asked if I am “done” writing about Cuba. I really don’t know. Each time

I visit the island I think this may be the last time. But then I start

picking up hitchhikers (I often travel by rental car and over the years

have picked up hundreds of people who represent a true cross-section of

Cuban society) I find that I am still a little in love with a society

where it is safe for everyone, even school children and pretty girls,

to hitchhike, and the poorest among them often reward me with a piece

of fruit or a cup of coffee when we reach their destination. There is a

great temptation to contrast their society with ours, and wonder

whether it is being a wealthy nation that makes us less safe and less

generous—or if there is something else that accounts for the difference.

How

did you

originally get involved in writing the Woman She Was?

On

cycling trips around Cuba I became fascinated with the untold story of

Celia Sánchez, whom I believe was the single person most responsible

for the success of the Cuban Revolution. I was touched by the

admiration Cubans today feel for her and how protective they are of her

memory. (She died in 1980.) It is not something they discuss readily

with foreigners. I would like to have written a biography about her,

but felt that would require my moving to Cuba for a year or more and I

couldn’t do that. So I decided on a novel about a modern Cuban doctor

who has been strongly influenced by Sánchez—a story entertaining enough

for vacation reading, while giving a sense of how Cubans live outside

the tourist zone; what their real issues are, and how they cope.

How did your perception

of Cuba change during the process of writing this book?

Not

while actually writing the book, but leading up to the decision to

write, it took a while to adjust to values in Cuba that are more or

less upside down to ones in our country. For example, in most places

trying to “get ahead” and better ones economic situation is laudable.

In Cuba, working for personal gain is okay, but not all that admirable.

Admirable is working for the good of the community. One jockeys to get

ahead if one must, but, well, there is a name for it: jinetero—jockey.

Someone who is trying to get ahead. In Cuba, this is also the word for

hustler or prostitute.

I took me a while to figure out that

Cubans are not into bargaining. They like to give you something, not

expecting (or pretending not to expect) payment. But they do expect the

receiver to reciprocate appropriately. An analogy would be our inviting

someone to dinner. We’d be offended if they offered to pay. But we’d

also be offended if, after a decent interval, they didn’t invite us to

dinner, or make some other reciprocal gesture.

What was the most

challenging part of writing this book?

Making

sure I got things right from the Cuban perspective. Naturally a dozen

fictional characters can’t reflect all the attitudes of all eleven

million Cubans, but it mattered a great deal to me that my characters’

thoughts, feelings, and concerns matched those of Cubans I know. An

example: First Worlders often suppose that the main problem for Cubans

is their government. But ask island Cubans what their main problem is,

and the majority will say “transportación.” My characters are ordinary

Cubans dealing with their issues, not ours; things like how often the

damned train breaks down between Havana and Santiago, or whether their

healthy college-bound teenagers are about to be (or have been) seduced

by tourists who might hurt them.

Do you have a favorite

extract or story or anecdote from the book?

This one is a bit long but works pretty well in terms of introducing

most of the characters:

Joe

had been about seventeen at the time. After hanging around with the

Cantú girls all his life, mostly lusting after Carolina, who was two

years older and only laughed when he tried to put the make on her, he

had just begun to notice her younger, shyer sister. That night he

followed Celia over to Joaquín's house to watch a rerun of televised

testimony by an ex-CIA operative, Philip Agee. Joe wasn’t much

interested, but it seemed a small price to pay for a little

touchy-feelie in the dark on the way home.

He assumed there

would be something in the program about the bomb planted on the plane

that killed the Cantú girls' father; that would be why Celia wanted to

see it. And so there was. However, Agee’s testimony also covered the

department store explosion that had broken his own dad. Agee claimed

that what blew El Encanto to smithereens was dynamite which CIA

operatives had stuffed into dolls in the store's stockroom. A few days

later, when Joe had time to assimilate it, he realised that that was

what made his mother and Kristina Cantú so tight. It wasn't just that

they were widows, but that they had been widowed by similarly

irrational (or purely evil) acts.

Standing there in the dark,

looking up at a window that glowed with pale blue light, it occurred to

Joe that Agee's testimony on TV that night had been a defining moment

for all of them. Naturally it hadn’t seemed so at the time. After all,

they were just a bunch of horny teenagers sprawled on a hardwood floor

in front of the TV, munching the plantain chips that Joaquín's mother

had fried up.

Joaquín had picked up a rapier and leapt

about the room making lightening thrusts at thin air, punctuating each

jab with, “Pendejo!” and "Take that, caca!” He had inherited his

father's quick reflexes and was already competing at a high level, but

it was when he started using fencing to vent his anger at the

sub-humans who had killed his father that he vaulted onto the Cuban

Olympic team. For awhile he and Celia were obsessed with all that crap,

using every scrap of news they could get their hands on to feed their

anger. Lucky for Celia she and Franci were so tight. Franci was always

telling Celia to let it go, and more than once got into it with Joaquín

for bringing it up all the time.

Thinking of Franci, Joe smiled

and absently scratched his crotch. He had had his eye on her, too, but

whenever he tried to put a move on her she brushed him off as if he was

a gnat. That night he had been sitting on the floor next to Celia, with

Franci sprawled on the other side of him. The program over, Franci

leaned on her elbow and mused on the psychology of the

terrorists—whether there was any way to prevent people from developing

into the type of zealots who had done the things Agee described in his

testimony. Her oversized Afro had brushed Joe’s arm, causing parts of

his anatomy to tingle.

Joe, wondering if he might make out

better if he ditched Celia and walked Franci home, had surreptitiously

slipped a hand up the back of her sweater. Franci sat up, looked deep

into his eyes, and said, “Please, José, try not to be a prick at a time

like this."

Luis, the oldest in the group, had adopted a certain

grim seriousness, causing him to look like a hard-line Cuban patriot of

the bureaucratic stripe, as their father had been and Luis would later

become. He had just begun attending Communist party meetings and might

have mouthed some Marxist cliché about the innate corruptness of

capitalism. Or maybe he hadn't said anything; Luis often didn't. In

that respect he was like a religious person who doesn't go in for

proselytizing. He believed deeply and practiced his beliefs, but rarely

talked about them.

As Luis brooded, Franci mused aloud, and

Joaquín leapt about the room imaginarily skewering the men who had

murdered his father, Celia and Carolina had sat holding hands, speaking

in low voices. Then Carolina had said, to the room at large, "I shall

join the army." And Celia said, "I would rather be a doctor."

As

for himself, that very evening Joe made up his mind to get the hell out

of Cuba by any means possible. Whatever his life turned out to be, he

sure as hell didn't want it to be a permanent target for the guys with

the biggest bombs.

What was the most

surprising thing you discovered about Cuba during the writing of this

book?

Not

while I was writing but while I was traveling in Cuba, I was constantly

surprised by the prevalence of cheerful, non-whiny children. I have

spent a lot of time in Third World countries, and have sneered at First

Worlders who could see only happiness in the smile of a tiny child

selling flowers on the streets of Mexico City; only a photo op in an

eight-year-old Mayan girl lugging an eight-month-old baby, and not the

misery that pervaded their (probably short) lives. I was not prepared,

in Cuba, to find such a huge number of genuinely happy children. Not

prepared for a culture where children really are the privileged class.

The Woman She Was is a novel loosely based on the life of the great

Cuban Revolutionary Comandante, Celia Sánchez. Sánchez (1920-1980) was

the organizing brain behind the Revolution, who ran the guerrilla bases

in the Sierra Maestra. Fidel’s secretary and reputed lover, she played

a central role in the Revolution and after, until her cancer death in

1980. Who knew that many attribute the organization and infrastructure

of the Revolution in the Sierra Maestra to her? It is said that she is

the one who picked Fidel to be the leader and spokesman of the M26

movement. Nevertheless she is almost unknown outside of Cuba. Extremely

modest, she shunned publicity. Even in death this was respected down to

an unmarked tomb in the Colon Cemetery in Havana.

The novel’s heroine is a contemporary Havana pediatrician, also called

Celia, who is unsure of which direction her life will take. Dr. Celia

is steeped in the spirit and revolutionary ideals of Celia Sánchez,

deeply patriotic and loving of her country and the Revolution. Nearly

every event, locale, and trend of any importance in Cuba during the

entire 53 years of the revolution are woven into the plot and

characterization of the book, contributing to the rich tapestry of this

fascinating read.

It is racily written with the hot sensuality of Cuba steaming through.

Can you imagine our heroine Dr. Celia “channeling ” Celia Sánchez,

making love to her beloved Fidel personified in a handsome mountain

research biologist at the Commandancia de la Plata historic site?

That’s where Celia and Fidel established the Sierra Maestra guerrilla

base at the start the Revolution. There are many twists and surprises

in this plot.

As a “Cuba Junky” I read every novel I can find set within the Cuban

Revolution. Most of them were only translated and/or published here

because they are part of the US Empire’s propaganda campaign of

sneering and lies about Cuba. This novel, however, is deeply

sympathetic to the people of Cuba and their ideals. It’s a good read

whether on the beach in Cuba or snowbound in wintry Canada.

Ken Dent lives in Vancouver. He has

made over 50 trips to Cuba, driven the country from end to end, and

explored many places in between.